“Language and culture cannot be separated. Language is vital to understanding our unique cultural perspectives. Language is a tool that is used to explore and experience our cultures and the perspectives that are embedded in our cultures.” -- Buffy Sainte-MarieLanguage reflects and recreates culture. Cultural attitudes become crystallized in language, which then serves to reinforce those cultural attitudes. It behooves us to carefully examine our language, to interrogate the meanings lurking within our everyday speech.

Take our sexual language, for example.1 The way we talk about sex speaks volumes about our cultural attitudes towards sex. I don't just mean the pervasive sexism of our sexual slang that reveals itself through the construction of women's bodies as dirty and the continued presence of the sexual double standard (Braun & Kitzinger, 2001; Schultz, 1975). I don't even mean the negative view of sex that becomes obvious whenever sexual terms are used as crude insults. Of course these themes are revealing and deeply troubling. But our cultural attitudes are also evinced through what is missing from our sexual lexicon.

Take a moment to think about the sexual words and phrases you know -- terms for parts of the body, sexual acts, all of it. (Go ahead; I'll wait.) Then think about what is *not* present in this sexual language. There are several important aspects of sexuality that get short shrift in our sexual lexicon.

[Note: Sexual terminology will be mentioned after the jump, so if you are offended by crude or explicit language, you may not wish to read further.]

Where is the love? Slang terms for sexual activity rarely reference intimacy or affection. Apart from euphemisms, slang terms tend to frame sexual activity in mechanistic terms. In one study of sexual slang, the most frequently provided terms for sexual intercourse were about evenly split between euphemisms (e.g., "doing it", "boff") and mechanistic terms (e.g., "bang", "screw") (Gordon, 1993).

This not only frames sex as entirely a mechanical act of body parts to the exclusion of emotional connection, but many of the mechanistic terms represent sex as violent or aggressive. Metaphors of tools or weapons are found among the slang terms for male genitalia (e.g., "tool", "sword") (Braun & Kitzinger, 2001; Cameron, 1992). "Fuck," the most frequently reported term for sexual intercourse in Gordon's (1993) study, is typically viewed as aggressive. Lest we think that such language is rarely used, Murnen (2000) found that 40% of male undergraduates indicated that they would use aggressive terms in discussing copulation in male-only or mixed-sex settings (men were more likely than women to use aggressive language, with only 17-19% of female undergraduates reporting that they would use aggressive terms in all-female or mixed settings, respectively). To be sure, sexual slang contains glancing references to love in the phrase "make love" and some of our genital slang (e.g., "love muscle", "love canal"), but such affectionate themes are rare.

What about pleasure? Sexual slang generally lacks any significant reference to pleasure. Again, there are a few references to pleasure in slang terms for genitalia (e.g., "pleasure pump", "Mr. Happy", "pink pleasure palace"), but these are infrequent. In Braun & Kitzinger's (2001) study of British genital slang, fewer than 1% of the terms provided were related to sex and pleasure. It interesting to note, too, the relative dearth of slang terms for the clitoris, given its centrality to women's sexual pleasure.

There are certainly slang terms for orgasm, but many of them focus on the physical aspects of ejaculation rather than the subjective sense of pleasure (e.g., "cream"). Very few of the common slang terms for orgasm specifically implicate pleasure, except indirectly through use of height or size as implied references to amount of pleasure ("climax", "big O").

In Christine Seifert's analysis of the phrase "get it in" as slang for sexual activity (used in rap songs and MTV programs such as Jersey Shore), she notes:

"But perhaps the most interesting thing about both the phrase and the activity it describes, in the context of Jersey Shore, is that no one talks about enjoying sex, or helping their partners enjoy it. Everyone just talks about 'getting it in' in the same manner they might talk about eating a sandwich -- it's nothing more than scratching a biological itch." (Seifert, 2011, p. 16)"Get it in." This perfectly captures the main themes of our sexual language. Sex is the act of bringing together male and female genitals in a mechanical or even violent fashion. The language of Jersey Shore "represents sex as nothing more than a boring game with body parts" (Seifert, 2011, p. 16). Gosh, doesn't that sound like loads of fun?

In part, this framing of sexuality as the dull exercise of getting genital Tab A into genital Slot B derives from our cultural legacy of equating sex with reproduction. If sex is only for the purpose of procreation, one would naturally focus on vaginal intercourse as the key activity. From this perspective intimacy and pleasure can easily be ignored as irrelevant to the fertilization process (although male ejaculation is essential to produce sperm, he doesn't need to enjoy the process). In other words, the emphasis on the reproductive functionality of sex excludes all the fun. The added layer of aggression most likely stems from our patriarchal traditions, as women have historically been legitimate targets for male aggression, particularly within intimate relationships.

"Language is not neutral. It is not merely a vehicle which carries ideas. It is itself a shaper of ideas." -- Dale SpenderWhat is the effect of our sexual language? I'm not arguing from a linguistic determinism framework; obviously, we still have the capacity to experience intimacy and pleasure through sex, even though our sexual language doesn't do justice to those aspects of our experience. Although language does not ultimately determine our subjective experience, it still has the potential to influence our experience.

"What we know or believe about sex is part of the baggage we bring to sex; and our knowledge does not come exclusively from firsthand experience: it is mediated by the discourse that circulates in our societies." (Cameron & Kulick, 2003 p. 15-16)More importantly, our language does not stand alone -- it reflects a broader cultural emphasis on sexual mechanics over intimacy. It is in the context of this cultural discourse that men's magazines emphasizes behavioral tricks (e.g., sexual technique) rather than effective intimacy-building efforts as the route to sexual enhancement (Spalding et al., 2010). Although we give lip service to the importance of intimacy and mutual pleasure as central to sexual experience, our primary discourse of mechanical reproduction contradicts (or at least undermines) the official story of loving, pleasurable sex.2

|

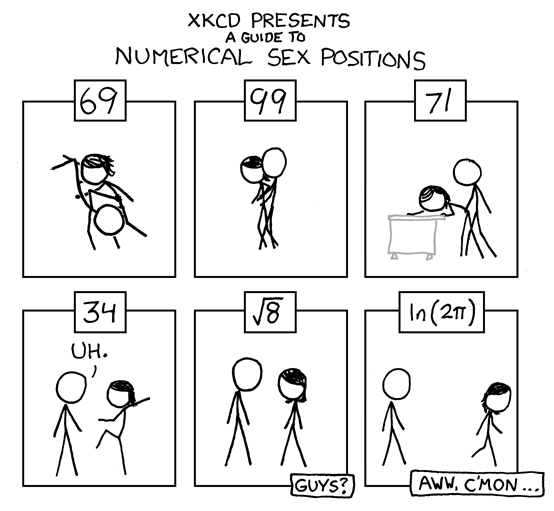

| XKCD: A Web Comic, by Randall Munroe |

I would argue that our cultural framing of sex as mechanistic coitus, devoid of intimacy or pleasure, has a number of problematic effects.

- It hinders intimacy. C. S. Lewis once said that, in dealing with sex, we are “forced to choose between the language of the nursery, the gutter, and the anatomy class.” In communicating with our partners about sex, our sexual language can be clinical ("I like it when you stroke my penis"), vulgar ("I like it when you stroke my cock") or infantile ("I like it when you stroke my pee-pee"). In short, our tone can be cold, crude, or juvenile, but nowhere in our language is there a mature, intimate, sexually explicit discourse. We have to invent that ourselves. While we can still have intimate sexual conversations, our language doesn't make it easy. In addition, I believe that the cultural marginalization of intimacy as a central component of sexuality makes it harder to admit our intimacy needs (particularly for men, as conventional masculinity discourages emotional openness and emphasizes the idea of sex as scoring).

- Genital functioning becomes the sine qua non of sexual satisfaction and dysfunction. If sex is all about bringing genitals together, then genital function becomes the litmus test of sexual functioning and satisfaction (Tiefer, 1991). By this logic, as long as you can get it up, get it wet, get it in, and get it off, the sexual encounter was a successful one. This ignores the subjective experience of the encounter, which is distinct from the performance of the individual body parts and is centrally important to the experience of sexual (dis)satisfaction. It is possible (and even common) for all the parts to be working and still have a problem in one's sex life; similarly, even with malfunctioning parts, one can still have a satisfying sex life. An emphasis on genital functioning as the sole measure of sexual adequacy also increases performance anxiety, which can itself cause sexual difficulties (as well as increasing sales of drugs like Viagra). Genital functioning is a poor measure of overall sexual satisfaction, which is influenced by many factors.

- It reinforces a heterosexist, intercourse-centric model of sexuality. By focusing on a mechanistic view of reproductive sex, our discourse reinforces the cultural sexual script that places intercourse as the main (or indeed, the only) sexual event worth noting. Obviously, this marginalizes all those who do not include vaginal intercourse as their main event, such as same-sex couples. In addition, it limits the sexual expression of couples who might well enjoy a broader menu of sexual activities, but feel that only intercourse counts as "real" sex.

- It limits sexuality education. Our cultural emphasis on the mechanics of reproduction hampers efforts to provide the comprehensive sexuality education that would prepare young people for effective sexual decision-making. Many sexuality educators have noted that sex education rarely includes significant mention of pleasure, particularly female pleasure, which undermines the development of sexual agency of young women (Allen, 2004; Fine, 1988; Fine & McClelland, 2006). Parents are also unlikely to include pleasure in their discussions about sex with their children, especially daughters (Martin & Luke, 2010). Intimacy, too, is marginalized in most programs; while many include an official message that sex should occur in committed relationships, there are few programs that offer systematic discussion of how to build intimacy or the realities of how sex and intimacy interrelate.

1 I will confine myself to discussing English sexual language here; the themes may or may not be similar in other languages and cultural contexts.

2 Cultural messages are complex and often contradictory. Pornography, for example, combines an emphasis on sexual mechanics with depictions of sexual pleasure, while intimacy continues to be ignored (Williams, 1989). There are certainly threads of cultural discourse about sexual pleasure and intimacy, but I still believe these are marginalized relative to the more general thrust of a mechanized view of sex. (Pun intended)

3 Some years ago, after recognizing how few terms specifically reference female masturbation, Q and I created the phrases "buttering the muffin" and "squeezing the sponge" (as in, "she can't come to the phone right now, she's buttering her muffin"). Similarly, Q's college dorm-mates wanted to have a female-active term for intercourse (most of the terms are male-active, as in "he nailed her"), so they invented the term "wet-mop" (as in "wet-mop me until my eyes bleed").

References:

Allen, L. (2004). Beyond the birds and the bees: Constituting a discourse of erotics in sexuality education. Gender and Education, 16, 151-167.

Braun, V. & Kitzinger, C. (2001). “Snatch,” “hole,” or “honey-pot?” Semantic categories and the problem of nonspecificity in female genital slang. Journal of Sex Research, 38, 146-158.

Cameron, D. (1992). Naming of parts: Gender, culture and terms for the penis among American college students. American Speech, 67, 367-382.

Cameron, D., & Kulick, D. (2003). Language and sexuality. Cambridge University Press.

Fine, M. (1988). Sexuality, schooling, and adolescent females: The missing discourse of desire. Harvard Educational Review, 58, 29-51.

Fine, M., & McClelland, S. I. (2006). Sexuality education and desire: Still missing after all these years. Harvard Educational Review, 76, 297-338.

Gordon, M. (1993). Sexual slang and gender. Women and Language, 16, 16+.

Martin, K. A., & Luke, K. (2010). Gender differences in the ABC's of the birds and the bees: What mothers teach young children about sexuality and reproduction. Sex Roles, 62, 278-291.

Schultz, M. R. (1975). The semantic derogation of women. In B. Thorne & N. Henley (Eds.), Language and sex: Difference and dominance (pp. 64-73). Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Seifert, C. (2011). Let's get it in: Making sense of Jersey Shore's sex slang. Bitch, 52, p. 15+.

Spalding, R., Zimmerman, T. S., Fruhauf, C. A., Banning, J. H., & Pepin, J. (2010). Relationship advice in top-selling men's magazines: A qualitative document analysis. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 22, 203-224.

Tiefer, L. (1991). Historical, scientific, clinical, and feminist criticisms of "The Human Sexual Response Cycle" model. Annual Review of Sex Research, 2, 1-23.

Williams, L. (1989). Hard core: Power, pleasure, and the "frenzy of the visible." Berkeley: University of California Press.

If you liked this post, here are some other posts you might find interesting:

The Meaning of Moaning

Why We Need Better Sex Education

World AIDS Day

Patriarchy Does Not Equal Pleasure: Sexism Makes for Bad Sex (Pt. 1)

Immersed in Pornographic History

Abstinence-Only Sex Ed: Biased, Inaccurate, AND Sexist

Reading, Reading

No comments:

Post a Comment