Reading Objects

"We need to develop the ability to suspend our reliance on conventional abstractions so that we can look at things anew, and in a careful, critical way. . . The capacity for fresh, critical observations is the basis of good research, and as your students advance in school that skill becomes increasingly vital. But being able to see the world clearly and to ask good probing questions of it is as important in a whole variety of non-academic life situations as well." (Shuh, Teaching Yourself to Teach with Objects, 1996, p. 7)

Shuh describes the process of reading objects by making careful observations and asking questions based on those observations (e.g., why? what are the implications?). He uses the example of a styrofoam cup, and through this process of interrogation, comes to see that:

"The Styrofoam cup has quite a story to tell if we’re able to listen. It’s a story that is not only about Styrofoam cups, but also about us, about some of our values and the choices that we make, about some of our limits and possibilities, and about some of the crises that characterize our world." (Shuh, 1996, p. 11)In other words, when read carefully, even seemingly trivial everyday objects can reveal a great deal about the culture from which they emerge.

Reading Portraits

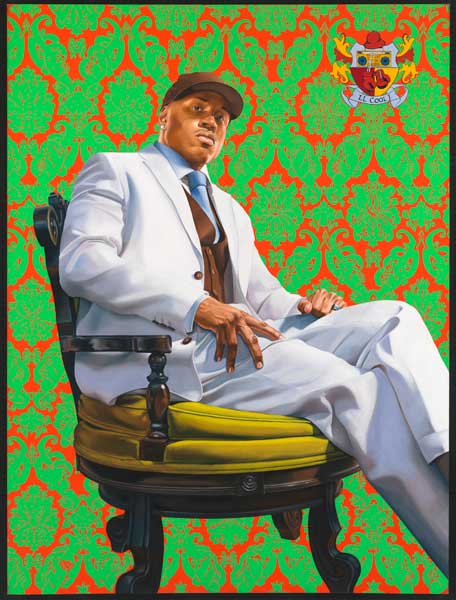

|

| LL Cool J Oil on canvas, Kehinde Wiley, 2005 |

Messages in the museum

The curators gave me greater awareness of the backstage of a museum exhibit. No longer did I view the museum as source of objective truth, a mere collection of objects to be scanned and dismissed. I began to see museum exhibits as intentionally created to convey a message to the viewers. The choice of objects and text, what was included and what was omitted, all emerged from the interplay of curators' motives and sociopolitical forces. Exhibits could be (indeed should be) critically examined and interrogated. The curators at the National Museum of the American Indian state this explicitly:"This gallery is making history and, like all other makers of history, it has a point of view, an agenda.What's found here is our way of looking at the Native American experience.What is said -- and what you see -- may fly in the face of much you've learned.We offer self-told histories of selected Native communities. Other communities, other perspectives would have produced different results. . .So view what's offered with respect, but also with skepticism.Explore this gallery.Encounter it.Reflect on it.Argue with it."-- Paul Chaat Smith (Comanche) and Herbert R. Rosen, Our Peoples: Giving Voice to Our Histories, National Museum of the American Indian

In keeping with the theme of the 2011 SFF cohort (The Politics of Identity: Race in 21st Century America), I created assignments that required my students to interrogate a museum exhibit representing a particular racial/ethnic group. After visiting one of the specified Smithsonian museum exhibits, they then wrote a paper in which they analyzed the objects, images, and text in the exhibit to illustrate how that racial/ethnic group was represented in the exhibit and what effect the exhibit would have on viewers' perceptions of members of that racial/ethnic group.My assignments

|

| Our Peoples exhibit at the National Museum of the American Indian (photo from virtualtourist.com) |

In fact, the students revealed excellent powers of observation in their discussions of the exhibits. They often commented on details that I had missed. For example, one student from my Psychology of Women class analyzed the representation of men and women in the African Voices exhibit. He noted in one of the sculpture displays that while the male figures were often depicted standing, "[m]ost of the women that were sculpted by the artist are in a kneeling position that is universally understood as a submissive stance. The only woman subject that is not kneeling is the 'Palm Wine Seller', that is only because she is balancing a basket of fruit on her head and nursing a child while traveling to the market, a multi task that would be difficult to carryout [sic] on one's knees" ("The Carver Among Us", African Voices). I had seen the exhibit four times and it had never occurred to me to consider the postures of the sculpted figures. Another student, observing that the initial photo display of Native Americans in Our Lives: Contemporary Voice and Identity included a diverse array of women of all ages and appearances, noted that this might have been influenced by the fact that there were female curators for this display. I hadn't noticed this fact, nor had I thought to consider the curators' gender as a factor influencing the display.

| ||

| Breakfast Photograph by Satomi Shirai, 2007 |

The students were also able to connect what they saw to broader sociocultural meanings, such as stereotypes. In analyzing representations of Asian-American men and women in the exhibit Portraiture Now: Asian American Portraits of Encounter at the National Portrait Gallery, one student provided this discussion of Breakfast by Satomi Shirai:

"The woman that is literally bending over backwards in front of the man might be a representation of how Asian American females figuratively bend over backwards for men in a society that values masculinity and denigrates femininity. . . While the fully clothed man is sitting in a seemingly comfortable position, the woman is completely nude and awkwardly balancing on a sphere. This somewhat suggests passive domination, which relates to the stereotype that Asian American women should be complaisant. Asian American women are challenged by their traditional role as quiet, obedient Asian woman [sic], or living up to expectations of stereotypical modern American woman who are [sic] more opinionated and independent. Although the woman in Breakfast depicts this struggle, Shirai does not seem to offer immediate resolution, emphasizing the currency of the issue and the notion that there is no definitive answer to the question of how Asian American women should behave in our society."It was clear from reading their papers that the students understood that these exhibits, objects, and images were intentionally chosen with particular communicative goals in mind. They grasped that the exhibits were shaped by the motives of the curator or artist to convey a particular impression.

"One thing that [African Voices] was trying to show about the African people was that they are becoming more modern of a continent and less isolated from the world. There was a display of money used throughout the different countries in Africa . . ."

"[Our Peoples] tells the tale of a people who had not only a wealth of gold and material goods, but also a wealth of culture. For example, on display was a great collection of beautiful golden artifacts created by Native Americans . . ."In both of these excerpts, the students articulate that the object (money or gold) reflected a choice on the part of the curator as part of trying to convey a particular message about the people being represented.

|

| Somali aqal in the African Voices exhibit, National Museum of Natural History |

|

| Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown © James Hinton, Collection of the Artist The Struggle for Justice, National Portrait Gallery |

The students also thought about the possibility that an object or image could have multiple possible effects or even mixed effects. Would this photo of Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown feed the stereotype of African-American men as aggressive, because of the presence of guns, or would it challenge that stereotype, due to their smiling faces and casual demeanor? In their papers, the students explored the question of whether the effect of a particular object or exhibit could differ across different audiences (e.g., depending on the pre-existing attitudes of the viewer).

"For example, people with high implicit racism may quickly view the picture of James Farmer to represent anger, whereas, I first perceived his facial expression as confidence." [The Struggle for Justice, National Portrait Gallery]

|

Copyright 1984, Estate of Alice Neel James Farmer Alice Neel |

Did it work? Yes!

"I sometimes rush too quickly through museums and this assignment made me slow down and appreciate all the items of an exhibit. Some of the things I will pay attention to are how the exhibits are laid out, who curated them, and how images and text are used and what message they are sending." (Montgomery College student enrolled in Psychology of Women)In short, the assignment was successful in fostering greater engagement with, and critical thinking about, the sociocultural meaning of objects and images and their implications. My students not only revealed more careful and thorough observations, but they also replaced unquestioning acceptance of the surface meaning of objects with an interrogation of the objects and images. This encouraged the students to be aware of the impact of their own choices of objects and images, for example in their self-presentation.

The assignment also increased the students' awareness of the active role of viewers in interpreting exhibits, objects, and images. Rather than assuming that viewers would receive the intended message, students understood that such messages could be lost, misinterpreted, or distorted. This led them to examine their own experience with the exhibits and consider how their preconceptions and beliefs might have shaped their interpretation of the objects and images. Quite a few students discussed what they learned from the exhibit as challenging their own stereotypes.

"Honestly, I thought that I entered the museum free of stereotypes [about Native Americans] . . . but that was not true. I actually found that my vision of Native Americans was limited to people with square shaped faces and olive skin. Fortunately as I was venturing through the museum, my view of the indigenous peoples of the Americas gradually changed. [. . .] Instead of looking at the color of a person's skin or the features that grace his or her face, I will celebrate the way that he or she may live, without hastily classifying such people into groups based on trivial outward differences." (Montgomery College student enrolled in Social Psychology)As an additional bonus, the students generally found the assignment highly engaging and meaningful. They enjoyed the trip to the museum and they often connected with the exhibits at a personal level, discussing the ways in which their experience was reflected in the museum exhibit.

"I was surprised to realize the type of impact that the assignment had on me as a whole. It seemed to be not only educational, but also personally applicable. . . Being a Hispanic minority in the United States, I can personally relate to many of the struggles that Asian Americans are faced with based on the literature and the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery exhibits. . . Perhaps the most fascinating part of this exhibit was the fact that all of the works were done by contemporary artists that were all Asian Americans. This makes the messages for the audience come from a unique autobiographical standpoint, which truly enriches the experiences. It's as if the artwork is telling a story that is based on true life, although it is often surreal and deeply captivating." (excerpts from one Montgomery College student enrolled in Psychology of Women writing about the experience)

Want to try it yourself?

This type of assignment could be used with objects or images brought into the classroom, online images, or other media. To be successful, though, preparation is key. It helps if the instructor is familiar with the item(s) to be analyzed, to effectively guide the interrogation. The instructor should also consider how the exercise fits into pedagogical goals. I tied my assignments to material on stereotyping to connect the exercise with psychological concepts and research, but instructors from other disciplines should tailor their assignment to fit their own discipline and pedagogy. It is also critical to prepare students, giving them the opportunity to practice interrogating objects and images. I found the experience of providing my students guided tours of the exhibit invaluable, as it helped me direct the students' attention and engage them with probing questions. For most people, the interrogation of objects and images is a new skill, and they will need support to develop these critical thinking skills. It is essential to engage in sustained interrogation of the objects or images, as this will result in deeper insight and critical thinking. Don't forget to help students notice what is missing, as well as what is present, in the objects and images. These lacunae can often be highly informative in the analysis. For example, students noted the lack of information about controversial historical events in the exhibits, and we discussed possible reasons for these absences.It behooves us all to develop the skills for careful observation and critical evaluation of the messages around us. Particularly in this, the information age, it is essential that we become more critical consumers of all types of information. So the next time you visit a museum, or look at an ad, or see a poster, look at it carefully. Think about it. Question it. Challenge it. You'll be surprised at what it tells you.

"I don’t see a trip to the museum as boring and tired now I see it as a [sic] enormous classroom with knowledge and fun. Next year I will take my whole family to the museum and share what I have learned from this experience. I want my son learn from gender and ethnicity and the reason curators set up the exhibits the way they do." (Montgomery College student enrolled in Psychology of Women)

References

Arnoldi, M. J., Kreamer, C. M., & Mason, M. A. (2001). Reflections on "African Voices" at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. African Arts, 34, 16-35.

National Portrait Gallery Education Department (2009). "Reading" Portraiture Guide for Educators.

Shuh, J. H. (1996). Teaching Yourself to Teach with Objects. In The Educational Role of the Museum. Eilean Hooper-Greenhill (Ed). Routledge, NY, pp. 80-91.

Smith, P. C. (2005). Presenting Evidence.

Stearns, D. C. (2012, January). Fostering critical thinking through interrogating museum exhibits. Paper presented as part of a panel entitled, Using the community in community college teaching: Dialogues on racial and cultural identity at the Association of Faculties for Advancement of Community College Teaching (AFACCT) conference, Rockville, MD.

Exhibits Discussed

African Voices, National Museum of Natural History, Washington DC.

Americans Now, National Portrait Gallery, Washington, DC.

Our Peoples: Giving Voice to Our Histories, National Museum of the American Indian, Washington DC.

Our Lives: Contemporary Voice and Identities, National Museum of the American Indian, Washington DC.

Portraiture Now: Asian American Portraits of Encounter, National Portrait Gallery, Washington DC.

The Struggle For Justice, National Portrait Gallery, Washington DC.

No comments:

Post a Comment